|

|

The text of the film “The fall of an empire—the Lesson of Byzantium”

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov)

Russian winter landscape. A church. A

snowstorm.

Narrator. Hello. In

1453, the Byzantine Empire fell. Let us now take a look at

how this happened.

Islamic chant weaves into the gusts of freezing

wind.

Instanbul. The muezzin continues his prayer, amplified

by a loudspeaker. The noise of a market place in a Middle

Eastern city. Turkish conversation.

Narrator. This city was once called

Constantinople; six centuries ago it was the capital city

of what was without exaggeration one of the greatest

civilizations in world history—the Byzantine Empire.

A rule by law, something we now take for

granted, was created here, based upon the Roman codes,

in Byzantium, 1500 years ago. A legal system which was

to become the basic foundation of all types of laws in

most modern governments was the monumental creation of

Byzantine jurisprudence during the reign of Emperor

Justinian. The system of elementary and higher

education first developed in Byzantium; it was here, in

the fifth century, that the first university appeared.

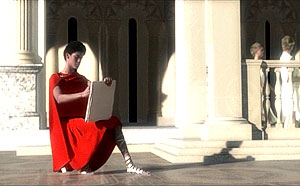

The most stable financial system in the history of

mankind was created in Byzantium, and existed in a

nearly unaltered form for over one thousand years.

Modern diplomacy with its basic principles, rules of

conduct, and etiquette was created and refined here, in

Byzantium. Byzantine engineering and architectural arts

were unrivalled. Even today, such famous works by

Byzantine masters as the domes of the Hagia Sophia

amaze the world with their technological perfection.

No other empire in human history lasted as long as

Byzantium. It existed for 1123 years. In comparison: the

great Roman Empire collapsed 800 after its establishment;

the Ottoman Empire fell apart after 500 years; the Chinese

Qing (or Manchu) Empire, after 300 years. The Russian

Empire lasted 200; the British, 150; the Austro-Hungarian

empire lasted around 100 years. During its height,

Byzantium was home to one sixth of the entire world

population. The Empire stretched from Gibraltar to the

Euphrates and Arabia. It encompassed the territories of

modern Greece and Turkey, Israel and Egypt, Bulgaria,

Serbia and Albania, Tunis, Algiers and Morocco, part of

Italy, Spain, and Portugal. There were around one thousand

cities in Byzantium—nearly as many as in modern

Russia.

|

|

The capital city’s incalculable

wealth, its beauty and elegance, amazed all the

European peoples, who were still barbarians at the time

when the Byzantine Empire was in its apogee. One can

only imagine—indeed, history records it as

such—how crude, ignorant Scandinavians, Germans,

Franks, and Anglo-Saxons, whose chief occupation at the

time was primitive sacking and pillage, after arriving

from some town like Paris or London (which had

populations of some tens of thousands) to this

megalopolis of millions, a city of enlightened

citizens, scholars, and elegantly dressed youths

crowding imperial universities, dreamt of only one

thing: invading and robbing, robbing and invading. In

fact, when this was actually accomplished in 1204 by an

army of Europeans calling themselves Crusaders, who,

instead of freeing the Holy Land treacherously sacked

the most beautiful city in the world, , Byzantine

treasures were carried away in an uninterrupted flow

over the course of fifty years. Hundreds of tons of

precious coin alone were carried away at a time when

the annual budget of the wealthiest European countries

was no more than two tons of gold.

|

|

Venice. The Cathedral of St. Mark. All the

columns, marble, and precious adornments were stolen at

that very time. By the way, those horses are from the

imperial quadriga, carried away from Constantinople by

the Crusaders.

Priceless holy relics and works of art were looted, but

even more taken by barbarians from Brussels, London,

Nuremburg, and Paris were simply destroyed—melted

down into coin or thrown away like refuse. To this day,

the museums of Europe are bursting with stolen Byzantine

treasures. But let us take into consideration that only a

small portion was actually preserved.

It was during this period of looting that the monstrous

modern lending system was created using treasures stolen

from Constantinople. This average sized city in

Italy—Venice—was the New York of the

thirteenth century. The financial fate of nations was

decided here. At first most of the booty was easily taken

by sea to Venice and Lombardy (the Russian word for

“pawn shop” to this day is

“Lombard”). The first European banks began to

spring up like mushrooms after a good rain. The English

and Dutch, more reserved than their contemporary Italians

and Germans, joined the activity a little later, and, with

the help of Byzantine riches pouring in, developed that

famous capitalism with its inevitable lust for profits,

which is essentially a sort of genetic continuation of the

sport of military plunder. The first significant Jewish

capital was a result of speculation in Byzantine relics.

An unprecedented flow of free money caused the Western

European cities to grow wildly, and became the decisive

catalyst in the development of craft, science, and the

arts. The barbaric West became the civilized West only

after it had taken over, stolen, destroyed, and swallowed

up the Byzantine Empire.

We must admit that our own Slavic forebears were no more

well-mannered, and also succumbed to the barbaric

temptation to get rich quick at the expense of

Constantinople’s seemingly inexhaustible wealth.

However, to their credit, and fortunately for us, their

lust for the spoils of war did not eclipse the most

important thing: Russians comprehended Byzantium’s

greatest treasure! This was neither gold, nor expensive

textiles, nor even art and sciences. The greatest treasure

of Byzantium was God.

Having traveled the world over in search of the truth and

God, Prince Vladimir’s ambassadors experienced only

in Byzantium that a true relationship between God and man

exists; that it is possible for us to have living contact

with another world. “We did not know whether we were

in heaven or on earth,” said the ancestors of

present-day Russians, astounded by their experience of

Divine Liturgy in the Empire’s most important

cathedral, the Hagia Sophia. They understood just

what kind of treasure can be obtained in

Byzantium. It was upon this treasure that our great

forebears founded not banks, nor capital, nor even museums

and pawn shops. They founded Rus’, Russia, the

spiritual successor of Byzantium.

So what made it possible for a nation so

great in the arena of world history, with such

extraordinary capabilities, to so suddenly begin to

lose its life force? What is most interesting is that

the problems Byzantium met during its period of

decline—aggression from foreign nations, natural

disasters, economic and political crises—were

nothing new for this over a thousand-year-old

government with its proven mechanism for getting out of

the most difficult situations. After all, the empire

had experienced all these things before, and had

overcome them.

Yes, there were many envious enemies both east and west,

there were earthquakes, there were plagues; but it was not

these which crushed Byzantium. All of these problems could

have been overcome if only the Byzantines had been able to

overcome themselves.

Today we will talk about that inner enemy which appeared

within the spiritual bowels of Byzantine society, and

broke the spirit of that great nation, turning it into a

helpless victim of those historical calls—calls

which Byzantium was no longer able to answer.

Nowadays we generally assess a

society’s well-being according to its economy.

Although the word “economics,” and even the

science of economics itself hales from Byzantium, the

Byzantines themselves never gave it much attention. The

Byzantine financial-economic system underwent several

serious crises during the course of history, but the

effectiveness of the Empire’s industry and

agriculture generally enabled it to weather the storms.

It suffices to say that for a thousand years, all

international trade was based upon the Byzantine gold

coin.

But Byzantium could not solve the problem of its

government’s loss of control over its own finances

and the huge, ungovernable process of capital flow towards

the West, to developing Europe, and this is what finally

destroyed its economy. The government dropped all levers

of trade and industry, and in the end gave all its trade

and industrial resources over to foreign entrepreneurs.

It happened like this: An important financial resource in

the country was not gas and oil, as it is now, but customs

obtained from the enormous international trade in the

Bosphorus and Dardenelles. The Byzantines, who earlier

relied solely upon their own capability to govern the

country’s economics, suddenly began heated

discussions about, and finally decided upon, consigning

the problems of international trade to their foreign

friends, who were more resourceful, and ready to take

responsibility for the expense of complex transport, armed

guards along trade routes, the construction of new ports,

and the intensification and development of commercial

activities. Western specialists were called in from Venice

and Genoa, towns which had grown large on several

centuries of Byzantine trade. They were granted duty-free

trade, and entrusted with the patrol of sea routes along

the Empire’s territory.

|

|

The West began by hook or by crook to lure

Byzantium into the formative prototype of unified

European trade organizations; and, taking advantage of

one of the most complicated periods in the life of the

Empire, succeeded in reaching its aim: Emperor Alexios

Komnenos signed an international trade agreement to the

Empire’s great disadvantage, called the

“Golden Bulla.” This agreement was in

actuality deceitful, and profitable only to the West.

At first everyone was pleased: the government saved a lot

of money that formerly went to its trade and military

fleets, trade increased, and the city’s shops and

markets overflowed with European and Asian products they

had never seen before. But this did not come without a

price. After just a few decades, domestic industry and

agriculture degraded sharply.

All the Byzantine traders either went bankrupt or became

dependent upon foreigners. When the country finally

realized what was happening, it was too late. The

“Golden Bulla” was annulled, and Emperor

Andronikos tried to reverse the flow of money back towards

his empire. He confiscated all foreign commercial

enterprises, which were draining the government of its

last resources. Both he and the country paid dearly for

this. He himself was brutally murdered; as for his

country… The republic of Venice, which had by that

time become a huge financial oligarchy, hired a whole

crusade, and sent it to sack Constantinople instead of

Jerusalem. The Byzantines, who had up until then

considered the crusaders to be in general brothers in the

faith and military allies, were so unprepared for such an

underhanded blow that it was unable to organize sufficient

defense. In 1204, French, German, and Italian contingents

of the Western union advanced upon Constantinople and took

it over. The city was mercilessly pillaged and put to the

torch.

|

|

At the same time Venice, considered then

to be the stronghold of free enterprise, announced to

the whole Western world that it was only restoring

disdained law and order and the rights of a free

international market; and mainly, it was warring with a

regime which denies all European values. This was the

moment when the West began to create an image of

Byzantium as a heretical “evil empire.” As

time went by, this image would continually be pulled

out for use from Western ideological arsenals.

Although Constantinople was recovered sixty years later,

Byzantium would never recover from the blow. Meanwhile,

foreign traders would retain complete control over both

the economy and the Byzantine market.

Another unresolved problem in Byzantium was corruption and

oligarchy. The government warred with them continually,

and was for a long time was effective. Bureaucrats and

financial schemers who had gone too far were punished and

exiled, their possessions completely confiscated and given

to the treasury. However, the authorities never really had

the strength and resolve to sever this evil

systematically. Oligarchs gathered entire armies under the

pretext of servants and guards, and plunged the government

into the thick of civil wars.

|

|

How did these oligarchs emerge in

Byzantium, and why did they become uncontrollable?

Byzantium had always been a strictly centralized

bureaucratic government; however, this was by no means

its weakness, but rather its historical strength. All

efforts to combine authority with personal interests

were cut off firmly and decisively. However, during one

moment in the period of political and administrative

reforms, the temptation arose to exchange the old and

seemingly awkward bureaucratic machinery for something

more effective and flexible, in which the

government’s role would be limited, and relegated

to that of an overseer of formal legalities. To put it

simply, the government, out of good intentions and with

its eye upon European experience, in fact willingly

relinquished a portion of its strategic monopolistic

functions, handing them over to small circle of

families.

However, contrary to the government’s expectations,

this new aristocracy it was feeding did not remain long

under the control of the bureaucratic apparatus.

Resistance continued with alternating success, and ended

in a serious political crisis, out of which the government

could escape only at the price of irreversible concessions

to foreigners. We know what happened after this. The

oligarchic corruption of the government continued up until

the very takeover of Constantinople by the Turks.

Incidentally, the oligarchs not only failed to provide the

government with money or arms during this final invasion

by the Turks, but even grabbed what little was left in the

treasury. When the young Sultan Mehmed met took the city,

he was shocked at the exorbitant wealth of some citizens

while the city’s army was completely lacking. He

summoned the richest citizens and asked them a simple

question: why they did not provide any money for the

city’s protection from the enemy? “We were

saving these funds for your Sultanic Majesty,” was

their flattering answer. Mehmed had them punished

immediately in the cruelest manner: their heads were

chopped off, and their bodies thrown to the dogs. Those

oligarchs who fled to the West hoping to hide their

capital were mercilessly fleeced by their Western

“friends,” and ended their lives in poverty.

A huge problem of the Byzantine government during the

period of decline was its frequent change in political

direction, which could be called a lack of stability and

succession in governmental powers. With each change of

emperors, the empire’s direction would often change

drastically. This weakened the country severely, and

cruelly exhausted the population.

Political stability is one of the most important

conditions for a strong state. This was the testament of

the great Byzantine emperors. However, they began to

disregard this testament. There was a period when a new

emperor was in power every four years on the average.

Could it have been possible under such conditions for the

country to undergo a revival, or complete any large-scale

state projects—projects which would have required

many years of systematic effort?

Of course, there were also very strong

emperors in Byzantium. One example was Basil II, who

was, by the way, Grand Prince Vladimir’s

godfather. He took on the Empire’s rule after a

serious crisis: the country had been practically

privatized by oligarchs. First of all, he took tough

measures to enforce a vertical power structure, quelled

all separatist movements in outlying territories, and

suppressed rebellious governors and oligarchs, who were

preparing to dismember the empire. Then he

“purged” the government, and confiscated

huge sums of stolen money.

Basil II’s strict measures allowed him to build the

state treasury to unprecedented sums—the

Empire’s annual income was ninety tons of gold

during his reign. As a comparison, Russia reached such

levels only towards the beginning of the 19th

century.

Basil significantly weakened the mighty regional

oligarch-magnates. These local sovereigns’ influence

and power were at times incomparably greater than that of

the official governors. Once, during a military campaign,

the Asia Minor magnate Eustaphios Maleinos demonstratively

invited Emperor Basil and his troops to rest at his

estate, and was easily able to accommodate this huge army

until they had sufficiently recuperated. This oligarch

seriously hoped to influence the country’s fate. He

began his intrigues, then moved his own puppet candidate

forward to the upper levels of authority. Later he would

pay dearly for this. All of his vast property was

confiscated, and he himself was sent to one of the most

distant prisons in the Empire.

After the rebellion of another magnate, Bardos Skleros,

was put down, Skleros even advised Basil II in a candid

discussion to exhaust the magnates with taxes, special

tasks, and governmental service, so that they would not

have time to get so rich and powerful.

Having restored the verticality of authority in the

country, Basil left a sort of “stabilization

fund” to his successor which was so large, that, in

the words of Michael Psellos, he had to dig new labyrinths

in the underground treasury stores. This national reserve

was designated first of all for military reforms and the

organization of a professional, capable army.

Basil’s successors, however, ineptly squandered this

reserve.

|

|

Byzantium in general had quite a problem

with her “successors,” although the

Byzantines were the greatest specialists in the world

in the area of royal succession. They did not have the

principle of inheritance to the throne. Wishing to

ensure that power succeed to a worthy heir, the

emperors usually chose one or two candidates, and

actively drew them into governmental affairs, delegated

high and responsible positions in the government to

them, and observed them. There was even a system

whereby the country would have at one time an emperor

and so-called junior emperors, the heirs. This was all

very reasonable, but no matter how well they honed this

system of succession, in the final analysis it became

clear that it was simply the luck of the draw.

Basil II was unlucky. Too occupied with governmental

affairs, he was unable to prepare a worthy successor, and

the throne passed to his natural brother Constantine VIII.

When the new emperor began to feel free, powerful, and

fabulously wealthy, he dedicated himself not to

governmental affairs, but rather to ecstatic daydreams

about accomplishments and glory which were supposed to

eclipse those of his brother. The results were sorrowful:

under the aegis of the dreamer in porphyry, the cynical

ruling elite quickly lost the obedience and discipline

cultivated by Basil II, and immersed themselves in power

struggles with renewed vigor.

Although the oligarchs quickly achieved their aim, it came

with a price. If Basil II punished insubordination by

confiscation of property, or, in extreme cases, by

blinding (a punishment not uncommon during the Middle

Ages), his successor, the hysterical Constantine, during

fits of anger, castrated half of his contemporary

Byzantine administrative elite. Furthermore, his

extravagance eclipsed even that of one of the most

dissolute emperors of the country’s period of

decline, whose nickname was “The Drunkard,”

and like him, in a state of inebriation, entertained the

rabble at the city hippodrome, three times larger than

this Roman Coliseum.

The next successor also failed to fulfill expectations.

The vertical, central power structure began to collapse.

The result of a new uprising amongst the clans and elite

and the continual re-shifting of property was predictably

deplorable—within fifty years the Empire found

itself on the brink of destruction.

|

|

The large stabilizing fund, in the hands

of inept sovereigns, caused more harm than

good—this money gained without effort began to

work against the country by corrupting society. The

same historian, Michael Psellos, remarked bitterly that

the empire “grew sick” from the misuse and

plunder of this money set aside by Basil. “The

government’s body,” he wrote, “became

bloated. Some were glutted with money; others were

stuffed to the gills with ranks, and their lifestyle

became unhealthy and destructive.

Thus, succession of power was a matter of life and death

for the Empire. When there is stability in succession and

development, the country has a future; without

stability—collapse. But the people did not fully

understand this, and kept demanding various changes.

Opportunists and run-away oligarchs also played on these

popular moods. They would usually hide somewhere abroad

and support various intrigues with the aim of overthrowing

this or that emperor who did not suit them, providing for

their own man and new re-assignments of property. Such an

individual was a certain Bessarion, a mediocre scholar,

unprincipled politician, and ingenious intriguer of the

15th century, who fled Byzantium for Rome and

received there political asylum. Bessarion coordinated the

entire opposition in Constantinople and caused no small

headache to the government. He went on further to become a

Catholic cardinal. He bought himself a house in Rome.

After his death, his Western protectors even named a small

street on the edge of town after him.

|

|

Another serious and incurable disease

never before a problem in Byzantium also developed: the

question of nationality.

The fact of the matter is that nationality problems in

Byzantium really had not existed for many centuries. As

the historical, lawful descendants of ancient Rome, which

was destroyed by barbarians in the fifth century, the

inhabitants of Byzantium called themselves Romans. In a

vast empire divided into many nationalities there was one

faith—Orthodox Christianity. The Byzantines

literally fulfilled the Christian teaching of a new

humanity living in a Divine spirit, where “there is

neither Greek, nor Jew, nor Scythe,” as the Apostle

Paul wrote. This hope preserved the country from the

destructive storm of ethnic conflict. It was enough for

any pagan or foreigner to accept the Orthodox Faith, and

confirm it in deed, in order to become a full member of

society. On the Byzantine throne, for example, were almost

as many Armenians as there were Greeks; there were also

citizens of Syrian, Arabian, Slavic, and Germanic origin.

Amongst the higher ranks of government were

representatives of all peoples in the Empire—the

main requirements were their competence and dedication to

the Orthodox Faith. This provided Byzantine civilization

with incomparable cultural wealth.

The only foreign elements for the Byzantines were people

who were strange to Orthodox morals and to the ancient

Byzantine culture and perception of the world. For

example, coarse, ignorant, money-grubbing Western

Europeans of the time were considered barbarian by the

Romans. Emperor Constantine VII, “The

Purple-born,” instructed his son when choosing a

bride, “Inasmuch as every nation has its own

traditions, laws, and customs, one should unite in

matrimony only with one from amongst his own

people.”

In order to understand the emperor’s thoughts

correctly, we must recall that his great grandfather was a

Scandinavian by the name of Inger, his grandfather was the

son of an Armenian man and Slavic woman from Macedonia,

his wife was the daughter of an Armenian man and a Greek

woman, and his daughter-in-law was the daughter of an

Italian king. His granddaughter, Anna, became the wife of

the Russian Prince Vladimir, just after the latter was

baptized.

The very idea of a “nation”

was actually a European concept which later in

Byzantium evolved into an idea of their own national

superiority (or more precisely, of that of the Greeks,

around whom Byzantium had grown). Europeans lived in

smaller states built upon ethnic principles; for

example, France, Germanic countries, and Italian

republics. National custom was good and correct for

them; but the fact of the matter was that Byzantium was

not an ethnic state, but rather a multi-national

empire, and this was an essential difference. For one

hundred years the Byzantines warred with this

temptation and did not allow themselves to be broken.

“We are all Romans—Orthodox citizens of the

New Rome,” they proclaimed.

It must be noted that this all unfolded at the very

beginning of the epoch called by historians the

“Renaissance”—the world-wide creation of

a nationalistic, Hellenic-Greek, pagan ideal. It was

understandably difficult for the Greeks not to be tempted

by this Western European renaissance, and the European

fascination with the culture of their great, ancient Greek

ancestors.

The first to give in were the intelligentsia. The

enlightened Byzantines began to sense their Greekness.

Nationalistic movements began, then the denial of

Christian traditions, and finally, during the reign of the

Paleologi, the imperial ideal gave way to a narrow,

ethnically Greek nationalism. However this betrayal of the

imperial ideal was costly—the nationalistic fever

tore the empire apart, and it was then quickly swallowed

up by the neighboring Moslem empire.

One apologist for Hellenic nationalism, the liberal

scholar Plethon, arrogantly wrote to Emperor Manuel II,

“We, the people whom you command and govern, are

Greeks by descent, as our language and educational

heritage testify!” Such words would have been

unthinkable even a century earlier. However, Plethon wrote

them on the eve of the fall of Constantinople, in which

were living people no longer Roman, but rather Greeks,

Armenians, Slavs, Arabs, and Italians, in enmity with one

another.

Greek arrogance led to the discrediting of Slavs in the

Empire. Byzantium thereby estranged the Serbs and

Bulgarians, who could have provided real help in the

struggle with the Turks. The result was that the peoples

of the once united Byzantium began to be at enmity with

one another.

|

|

The West did not miss the chance to take

advantage of this new problem: it began to forcefully

convince the Serbs and Bulgarians that the Greeks have

been suppressing their national identity for centuries.

Several real revolutions were provoked, and finally,

with the help of economic and military forces, the West

insisted upon the Serbs’ and Bulgarians’

separation from Byzantium and unification with Latin

Europe. These nationalities took the bait, exclaiming

suddenly, “We are also Europeans!” The West

promised them material and military aide, but of

course, deceived them, instead throwing them cynically

before themselves as a buffer along the warpath of the

Turkish hordes. The Balkan states, so loyal to the

West, found themselves under the cruel Turkish yoke for

many long centuries. And Byzantium was no longer able

to help. National arrogance thus played a wicked role

for the empire.

Another great problem was the gradual loss of control over

the far-flung provinces. The contrast between the

provinces and the satiated, wealthy capital,

Constantinople, which lived for the most part at the

expense of these impoverished areas, became very sharp. At

the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Byzantine

writer Micheal Choniates wrote to the capital’s

inhabitants in bitter reproach, “Do not all riches

flow into the city as rivers into the sea? But you do not

wish to take a look at the towns around you, who await

some fairness from you. You send them one tax collector

after another with brutish teeth, in order to devour their

last morsels. You yourselves remain in your city to enjoy

your peace, and extract the riches.”

Even the capital city’s chief administrator, the

eparch of Constantinople, enjoyed a particular status in

the country, and his contemporaries often compared his

power with that of the Emperor, “only without the

purple,” as they would say. One such eparch once

became so feverishly involved in the building of high-rise

buildings in the capital that he could only be stopped by

a special imperial order forbidding the construction of

buildings over ten stories.

All political, cultural and social life essentially took

place in Constantinople. The government did not wish to

notice that a serious imbalance was developing, and the

forsaken provinces were becoming more and more decayed.

Gradually, the tendency to flee to the center became

increasingly marked.

Governors of these distant territories

also played their deceitful games. Money budgeted and

sent to the provinces was shamelessly expropriated. It

would not have been half so bad if this stolen money

had gone only towards the enrichment of governors and

their proteges. But the money was often used to create

real armies under the guise of peace officers. These

battalions were often more capable in battle than the

regular army.

When the government weakened, the provinces separated. The

government watched this process unfold almost helplessly.

But the rebellious governors, having freed themselves of

central authority, were not long to remain captivated by

their own high hopes. Together with their hapless

population, they almost immediately fell prey to the cruel

authority of the non-Orthodox. When this happened, the

local population was usually destroyed completely, and the

region re-settled by Turks and Persians.

The demographic problem was one of the most serious

problems in Byzantium. The Empire was gradually inhabited

by peoples of a foreign spirit, who firmly supplanted the

native Orthodox population. The country’s ethnic

composition changed visibly. This was in some ways an

irreversible process, for the birth rate in Byzantium was

decreasing. But this was not the worst thing. Something

similar had earlier occurred periodically. The catastrophe

was that the peoples who were pouring into the Empire were

no longer becoming Romans, as they once had done, but

remained permanently foreign, aggressive, and enemy. Now

the newcomers treated Byzantium not as their new homeland,

but only as potential property which should sooner or

latter come into their own hands.

|

|

This happened also because the Empire

refused to educate the people—a concession it had

made to the new, renaissance-era demagogy declaring

state ideology to be a violation of the individual.

However, nature abhors a vacuum. Having voluntarily

renounced their thousand-year ideological function of

educating and cultivating the people, the Byzantines

made way for influences upon the minds and souls of

their citizens; influences which were not so much a

promotion of independent and free thinking as they were

a form of intentional ideological aggression, aimed at

destroying the foundations of state and society.

But the Byzantines had amazing, incomparable experience!

The best leaders of the Empire were capable of using their

vast inheritance—a wealth of experience in

governance and subordination. As a result of this acumen,

cruel barbarians, after partaking of the great Christian

culture, became the most reliable allies, received

grandiose titles and vast estates, were numbered amongst

the highest ranks of government service, and fought for

the interests of the Empire in the furthest stretches of

its territory.

As for demographic issues, and the eternal headache of any

empire—separatism in the outlying areas—the

best Byzantine Emperors left as an inheritance proven

methods of solving these issues; for example, creating

conditions for the massive resettlement of the inhabitants

of centralized areas to the outlying provinces. This would

quickly spark an explosion in the birth rate, and

effectuate an extraordinary adaptability to the new

locality in the second generation.

However, this wealth of experience was cruelly mocked and

criminally disregarded in favor of foreign opinion; and,

finally, it was irretrievably lost!

But just what was this invasive opinion? Whose views did

the Byzantines begin to value? Who was able to so

influence their minds that they began to commit such

suicidal mistakes, one after another? It is hard to

believe that such enormous reverence and dependence could

have developed with regard to that same once barbaric

West, which had for centuries so enviously and greedily

looked upon Byzantium’s wealth, and then coldly and

systematically grew fat upon its gradual dissolution.

|

|

Byzantium was a unique state which

differed from both the East and the West. Everyone

recognized this fact; some were exhilarated by it,

others hated this independence, while others felt

oppressed by it. Be this as it may, Byzantium’s

difference from the rest of world was an objective

reality. First of all, Byzantium was the only country

in the world which stretched over a huge territory

between Europe and Asia, and its geography was already

a large contributing factor to its uniqueness. It is

also a very important fact that Byzantium was a

multi-national empire by nature, in which the people

felt the state to be one of their highest personal

treasures. This was entirely incomprehensible to the

Western world, where individualism and personal

self-will had already been raised to the status of

sacred principle.

Byzantium’s soul, and its meaning of existence, was

Orthodoxy—the unspoiled confession of Christianity,

in which no dogmas had changed essentially for a thousand

years. The West simply could not endure such demonstrative

conservatism, called it undynamic, obtuse, and limited; it

finally began with grim fanaticism to demand that

Byzantium modernize her whole life in the Western

image—first of all in the religious, spiritual

spheres, and then in intellectual and material spheres.

With respect to the uniqueness and particularity of

Byzantium, the West, despite its occasional raptures over

Byzantine civilization, pronounced the sentence: it must

all be destroyed; if necessary, together with Byzantium

and her spiritual inheritors.

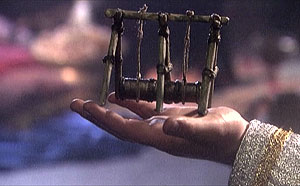

Not a bad organ. Also invented and created in Byzantium.

In the ninth century it was brought here to Western

Europe, and from that time on, as you see, it has taken

root.

Of course, it is senseless to say that the West was to

blame for Byzantium’s misfortunes and fall. The West

was only pursuing its own interests, which is quite

natural. Byzantium’s historical blows occurred when

the Byzantines themselves betrayed their own principles

upon which their empire was established. These great

principles were simple, and known to every Byzantine from

childhood: faithfulness to God, to His eternal laws

preserved in the Orthodox Church, and fearless reliance

upon their own internal traditions and strengths.

For hundreds of years, Byzantine emperors

both wise and not so wise, successful governors and

inept commanders, saints on the throne and bloody

tyrants, when faced with a fateful choice, knew that by

following these two rules they ensure their

Empire’s ability to survive.

In the Holy Scriptures, which every Byzantine knew, this

is stated very specifically: I call heaven and earth

to witness before you this day: I have offered you life

and death, blessing and curse. Choose life, that ye might

live, and your descendents also (Deut. 30:19).

In Byzantium, after the end of the 13th

century, two parties emerged—one called for reliance

upon the country’s internal strengths—to

believe in them unconditionally, and to develop the

country’s colossal potential. It was prepared to

accept Western European experience discriminately, after a

serious test of time, but only in those cases where such

changes would not touch the fundamental basics of the

people’s faith and state politics. The other

party—pro-Western—whose representatives

pointed to the indubitable fact that Europe is developing

more rapidly and successfully, began to proclaim more and

more loudly that Byzantium has historically exhausted

itself as a political, cultural, and religious phenomenon,

and to demand a root-level re-working of all state

institutions in the image of Western European countries.

Representatives of the pro-Western party, secretly, or

more often, openly supported by European governments, held

an undoubted victory over the imperial traditionalists.

Under their guidance, a series of important reforms took

place, including those economic, military, political, and

finally, ideological and religious. All of these reforms

ended in total collapse, and lead to such spiritual and

material destruction in the Empire that it remained

absolutely defenseless before its Eastern

neighbor—the Turkish Sultanate.

|

|

First of all, the pro-Western party began

to re-evaluate its fatherland’s history, culture,

and Faith. However, instead of healthy criticism, they

offered only destructive self-abnegation. Everything

Western was exulted, and everything of their own was

held in contempt. Byzantine history was distorted,

faith and tradition were mocked, and the army was

degraded. The whole of Byzantium began to be painted as

a sort of universal monster.

The wealthy Byzantine younger generation no longer studied

in its own country, but rather left to study abroad. The

best minds of Byzantine science emigrated to the

West—the state ceased to give them the proper

attention. Emperor Theodore II foretold, “Rejected

science will become our enemy and will take up arms

against us. It will either consign us to destruction, or

turn us into barbarians. I write this in a state of gloomy

melancholy.” The Emperor’s presentiment did

not deceive him. During the final, fatal attack on

Constantinople, a brilliant metal-casting scholar, a

Hungarian named Urban, offered to create for the Emperor

large artillery armaments which could sweep away the

Turkish troops. But the treasury was empty, and the rich

of Constantinople did not give any money. Not having

received payment, the insulted Urban offered his services

to Sultan Mehmed. The Sultan seized the opportunity which

would give him the capability to destroy the city’s

invincible walls. He provided unlimited funds and began

the project. Finally, the canons of Urban, the best

student of the Byzantine ballistics school, decided the

Empire’s fate.

|

|

Western reforms in the military along

Western lines had begun long before this. In Byzantium

there had for many centuries existed a proven, although

not always effective system called stratiotes—a

national regular army with mandatory service from the

age of eighteen. With time, the Byzantine army

underwent serious changes. An army of the new type

required significant capital. The very stabilization

fund of Basil II was earmarked precisely for the

creation of an effective army. The fund, as we recall,

was squandered, while decisions were made to totally

re-vamp the army according the image of a Western

professional one. At that time, the Byzantine mind was

captivated by the image of Western knights, all nailed

into suits of armor—the latest achievement of

contemporary military industry. “My Byzantines

are like clay pots,” one emperor commented

contemptuously about his warriors, “but the

Western knights are like iron kettles!” To be

brief, as a result of the reforms, they took apart

their regular army, but never built the professional

one. In the final analysis, they took the course of

forming a block with the West within the framework of a

new military-political union. In practice this meant

that during the most critical periods of war they were

forced to resort to a professional army, but not of

their own—to a mercenary one. What it means to

have a mercenary army, how loyal and capable it is, the

Byzantines learned by very bitter experience.

Attempting to rely on the West’s experience, the

state became more and more ineffective. Even so, they

stubbornly sought salvation in a new imitation of Western

examples.

The final and most devastating blow to Byzantium was the

ecclesiastical union with Rome. Formally, this was the

submission of the Orthodox Church to the Roman Pope for

purely practically reasons. One after another aggressive

attack from foreign nations forced the country to make the

choice: either to rely on God and their own strengths, or

to concede their age-long principles upon which their

state was founded, and receive in return military and

economic aide from the Latin West. And the choice was

made. In 1274, Emperor Michael Paleologus decided upon a

root concession to the West. For the first time in

history, ambassadors from the Byzantine Emperor were sent

to Lyon to accept the supremacy of the Pope of Rome.

|

|

As it turned out, the advantages the

Byzantines received in exchange for their ideological

concession were negligible. The pro-Western

party’s calculations not only were unjustified,

they collapsed. The union with Rome did not continue

for long. The Grecophile Pope Leo IV, who had drawn

Byzantium into the Union out of better intentions, died

soon after the Union was concluded, and his successor

turned out to be of a completely different spirit: the

interests of the Latin West were first on his list. He

demanded that Byzantium change completely, that it

re-make itself in the image and likeness of the West.

When these changes did not happen, the Pope

excommunicated his newly-baked spiritual son, Emperor

Michael Paleologus, and called Europe to a new crusade

against Byzantium. The Orthodox converts to Catholicism

were pronounced bad Catholics. The Byzantines were

supposed to get the point that the West needed only

complete and unconditional religious and political

submission. Not only the Pope was to be recognized as

infallible, but the West itself as well.

Another terrible loss from betrayal of the Faith was the

loss of trust amongst the people in the government. The

Byzantines were shocked by the betrayal of their highest

value—Orthodoxy. They saw that it is possible for

the government to play with the most important thing in

life—the truths of the Faith. The meaning of the

Byzantines’ existence was lost. This was the final

and main blow which destroyed the country. And although by

far not all accepted the Union, the people’s spirit

was broken. In place of their former thirst for life and

energetic resolve to action, there appeared a terrible

general apathy and fatigue. The people no longer wanted to

live.

This horror has happened during various periods in

history, with various peoples, and with entire

civilizations. This is how the ancient Hellenic people

died out, amongst whom an inexplicable demographic crisis

occurred during the first centuries A.D. People did not

want to live; they did not want to continue their

generation. The rare families that did form often had no

children. The children who were born died from a lack of

parental care. Abortions became a ubiquitous practice. The

darkest occult and Gnostic cults came aggressively to the

forefront—cults characterized by hatred for life.

Suicide became one of the main causes of death amongst the

population. This conscious dying out of a population has

been called by science “endogenous psychosis of the

I-III centuries”—a mass pathology and loss of

meaning for continued existence.

Something similar happened in Byzantium

after the conclusion of the Union. The crisis in state

ideology led to total pessimism. Spiritual and moral

decline began to take over, along with unbelief,

interest in astrology, and the most primitive

superstitions. Alcoholism became a true scourge of the

male population. A morbid interest in long-forgotten

mysteries of the ancient Greeks arose. An

intelligentsia fascinated with neo-paganism consciously

and cynically destroyed the foundations of Christian

Faith in the people. Processes of depopulation and

family crises ensued. Out of the 150 Byzantine

intellectuals known to us to have lived during the late

14th, early 15th centuries, only

twenty-five had families of their own.

This is only a small part of what came to Byzantium due to

the decision amongst the elite to sacrifice higher ideals

for the sake of practical advantages. The soul collapsed;

in a great nation, who had given the world grandiose

examples of flights of spirit, now reigned unbridled

cynicism and squabbles. One Russian pilgrim wrote bitterly

during the mid 14th century, “Greeks are

those who have no love.”

The best minds of Byzantium watched with sorrow as the

Empire gradually died, but no one heeded their warnings.

The high profile statesman, Theodore Metochites, who saw

no salvation for Byzantium, wept over the former greatness

of the “Romans” and their “perished

happiness.” He lamented the Empire “wasted by

illnesses, easily succumbing to every attack by its

neighbors, and become the helpless victim of fate and

eventuality.”

A new Union signed in Florence, in what

was now a completely mad hope for help from the West,

did not change a thing. For the Byzantines themselves

this was a new moral blow of great magnitude. Now, not

only the Emperor, but even the Holy Patriarch shared

the faith of the Latins.

However, despite various hierarchs’ betrayals, the

Orthodox Church stood firm. “All were against the

Union,” a Byzantine historian relates.

“O, piteous Romans!” monk Gennadios Scholarios

wrote prophetically from his reclusion after the signing

of the Florentine Union, and fourteen years before the

fall of Constantinople. “Why have you gone astray

from the right path? You have departed from hope in God

and begun to hope in the might of the Franks. Together

with the city, in which everything will soon be destroyed,

have you apostatized from your piety? Be merciful to me, O

Lord! I witness before the face of God that I am not

guilty of this. Return, wretched citizens, and think about

what you are doing! Together with the captivity which will

soon befall us, you have apostatized from your

fathers’ inheritance and begun to confess dishonor.

Woe to you, when God’s judgment shall come upon

you!”

The words of Gennadios Scholarios came true to the letter.

And he himself was to carry the unbearably heavy cross of

a bitter patriarchate—he became the first Orthodox

patriarch in Constantinople after its fall to the Turks.

The fatal year of 1453 was approaching. In

April, Sultan Mehmed, still a very young man of

twenty-one, about the age of a college sophomore in

todays’ Istanbul, attacked Constantinople. The

Sultan was absolutely delirious with the idea of taking

the Romans’ capital. His elder

councilors-viziers, one of whom was a secret agent from

Byzantium, persuaded him to cancel the attack, saying

that it was too dangerous to battle on two fronts, for

all were certain that battalions from Genoa and Venice

would arrive any minute. But the Sultan turned out to

be a disobedient pupil.

The promised help from Europe, of course, did not arrive.

To the party of Westernizers in Constantinople there was

also added a pro-Turkish party. Sad as it may be, there

was no true Byzantine-imperial party amongst the

politicians.

The Turkish party was headed by the first

minister and admiral, Grand Duke Notaras. He announced

for all to hear that “It would be better to see

the Turkish chalma cap ruling in the city than the

Latin tiara.” A little later he, the first

minister, was to fully experience just what this ruling

Turkish chalma cap was actually like. When Sultan

Mehmed II took the city, amidst the general pillage and

wild mayhem, he decided to appoint this very Notaras as

head of the city. However, when he learned that the

Grand Duke had a fourteen-year-old son of rare beauty,

he demanded that the son be first surrendered to his

harem of boys. When the shaken Notaras refused, the

Sultan commanded that both he and the boy be beheaded.

The terrible outcome was unfolding inescapably.

O Heavenly King, Comforter, Spirit of Truth, Who art

everywhere present and fillest all things, treasury of

good gifts and Giver of life, come and abide in us, and

cleanse us of all impurity, and save our souls, O Good

One.

Narrator. May 29, 1453, after a

siege lasting many months and resisted heroically by

the city’s defense forces, the Turks were able

to break through the upper wall. The defense forces,

frightened, turned to flight. The last Byzantine

Emperor, Constantine Paleologus, remained alone,

abandoned by all. Holding his sword and shield, the

Emperor exclaimed, “Is there not a Christian

who might take off my head?” But there was no

one to answer. The enemies surrounded him, and after

a brief siege, the Turks standing behind the

sovereign killed him with a knife in the back.

Modern Istanbul. The streets of the city. The chant of

the muezzin.

Narrator: (walking through the

city): What more is there to say?... Now a completely

different people are living here, with different laws and

morals. The Byzantine inheritance, foreign to the

invaders, was either destroyed or altered at the root. The

descendents of those Greeks who were not destroyed by the

conquerors were made into second class citizens in their

own land, with no rights, for many long centuries.

A Western advertisement in Istanbul.

The West’s vengeful hatred of Byzantium and her

successors is entirely inexplicable to the West itself; it

goes to some deep genetic level, and—as paradoxical

as this may seem—continues even to the present day.

Without an understanding of this amazing but undeniable

fact, we risk misunderstanding not only distant history,

but event historical events of the twentieth and

twenty-first centuries .

In Russia, before the revolution, serious research on

Byzantium was conducted. However, the necessary

conclusions were not drawn from purely theoretical

knowledge…. During the first decades of soviet

government, research in Byzantology was cut off, and then

officially banned. More than that: just in case, the

Bolsheviks repressed all Byzantologists remaining in

Russia; only a few were able to flee abroad.

Research in Byzantology was re-opened in

Russia by a decision from the highest governmental

levels. In 1943, at Stalin’s orders, the

Institute of Byzantology was created, and a

corresponding cathedra in the Moscow State University

was opened. Was there no other time than 1943 to open

such an institute? It is simply that the former

seminarian, Joseph Dzhugashvili, finally understood

from whom they should be studying history.

And the great city of Constantinople, which had oft times

forgotten the ancient laws of its fathers, for which

forgetfulness it did not even preserve its own name,

peforms if only its final service as an instructor, to

retell the story of its greatness—and of the

monumental fall of a great empire.

The chanting of the muezzin over Constantinople grows

louder. The sound of a Russian snowstorm blends into

it.

We are again before a snow-covered Russian church.

With it in the background is heard the prolonged chanting

of the muezzin and the snowstorm. The chanting gradually

disappears. The snowstorm.

|